Love as Committed Singularity

"I have nothing to say on love. At least pose a question. I'm not capable of talking in generalities about love."

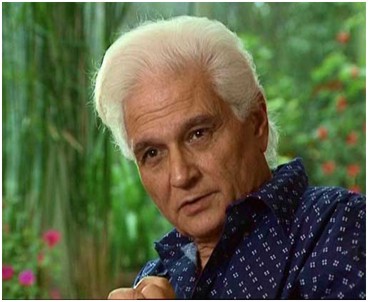

Jacques Derrida

Philosophy, it seems to me, is a study of asking good questions and reflecting through the answers, which in turn lead to more good questions. It is, in other words, an elementary yet elemental dialectic of human thought. Of course, we'll never get to the point of being "good" at this. True philosophers, thus, only know that they are never good at philosophy. Nonetheless, to ask good questions and to arrive at good answers comprise an important "skill," an important part of being human. In our highly technological age, we prize quick answers, but quick answers do not promise quality. Dare I suggest, the day we fail to ask questions is the day we deny our humanity and proceed to becoming biological robots. To be alive is to engage in such a dialectic. Even for a subject such as "love," we must abandon our initial preconceptions - particularly if they come from Hollywood first - and start anew.

The great French deconstructionist, Jacques Derrida, was asked once to talk about love, a question that he found utterly inadequate because it was not questioned. The interviewer, in other words, simply told him, "Talk about love." We all assume that we know what love is, and I think part of that comes from the fact that many of us were and still are loved by someone. Very few of us can deny that our parents loved and still love us. But we don't know why aside from the fact that for most of our knowledge, they loved us. Sure, they supported us, and all, but don't good pastors support us too? What makes the love of a pastor different than the love of a parent? Some of my readers have engaged in dating relationships before and broken up. Was that love? Did your significant other not commit him/herself to you until some noteworthy event caused the breakup? Is the love of a father the same as the love of a mother?

But Derrida makes an important distinction in the inquiry on love. He differentiates the love tied to singularity (e.g. I love you because you are you) and the love associated with the qualities of the beloved (e.g. I love you because you have X attributes, or Y characteristics, etc.). The latter, of course, is something I don't wish to pooh-pooh, but it risks delving into some utilitarian calculus. I love you because your attributes somehow fit into my utility function. If that is quite so, then we must cease questioning love and simply search for "Mr. Right" or "Ms. Right," "Right" being defined as the one who best fits the other's utility function. In such a situation, sexual morality is an unnecessary exercise. Whoever is Right now, may be Wrong later. Thus, the institution of divorce is made easy in order that everyone can "search" the sexual market for Rights that shift with one's changing tastes and preferences. In other words, love ceases to question; it becomes solely a matter of compatibility. This, I consider, is not that much different than making sure your American ~120 V plugs do not get plugged into a ~220 V plug in Singapore. It's not hard - just buy a transformer, plug it in, and off you go. If love is merely compatibility, a complex calculation of marginal utilities, then you rely on superficialities. Love becomes a simple matter of "plug and play." C'est laissez faire et laissez passer.

Love as a singularity, however, is much more complicated. Let us consider the example of a good engineer. Now, contrary to established definitions, a good engineer is not one who does the job well. That denigrates engineering to the latter utilitarian conception. Quite oppositely, a good engineer is one who loves engineering for its own sake. Something inexplicably alluring exists within engineering that makes the field worth expending one's health on. To love engineering is to pore through the symbologies and the vocabulary, to chew it and let it be part of you. To speak in languages of Laplace operator and Fourier's laws becomes second nature and is enjoyable, not because others "ooh" and "aah" at you, but because its thought quickens your heart. It, thus, motivates us to question, to question further, because the engineer's love for the subject makes the subject so desirable that he or she desires for it to reveal more of itself. Yes - there is an erotic component to it (erotic alluding to the notion of savoir faire as opposed to the pornographic conception). The good engineer beckons Engineering to unclothe itself, even force itself back on the engineer.

No doubt my description may sound utterly insane and silly. But love must be silly. It must be messy. It must be inexplicable. It has jouissance coursing with its veins because you desire it, and it desires you back. Yes, good Engineering is erotic. It is incomprehensible for someone like me, I who have no idea what's so amazing or alluring about engineering. It is befuddling to someone who can care less about the Heat Equation. I should note, by the way, that there's nothing shameful about the erotic. We must abandon our Victorian notions that suggest that public discussions on sex is inappropriate. Why not? Is it something that is rare and somehow bad that it cannot be discussed? No. We want to de-exoticize sex so that it loses its superficial allure - that found in pornography and other debased forms of sex - and rises to become erotic love. Indeed, humans are erotic creatures. It is when we lose our erotic side that we become consumed with lust and hatred. Without our erotic dimension, we search for the existential side of us that is not. We drink, but don't enjoy; we eat, but don't savor; we find manhood/womanhood, but will only find hollowness.

With all this in mind, let us ask what it means to "love Jesus."

Evangelicals love to "love Jesus." We place it on our Facebook statuses all the time, falsely imagining that by doing so, we declare our love for Jesus, and therefore in declaring our love for Jesus, we are affirming to ourselves that we indeed do love Jesus. I love Jesus because I have told the world I love Jesus. The rhetoric that goes with loving Jesus often goes: "I love Jesus for what he has done on the cross for us."

This is not loving Jesus as singularity. This is loving Jesus as a utility. The latter suggests that had Jesus not died on the cross, we would not love him. This is, of course, befuddling, because I would wager there were biblical figures who, indeed, "loved Jesus" before he even died on the cross. But secondly, such a logic feeds into the utilitarian mindset. It's not that difficult to make a further claim that because Jesus died for us out of love for us, he desires what's good for us. Our faith, then, is not embedded in the deity-cum-personhood of Jesus, but in the contingencies of Jesus. We love Jesus for the material benefits associated with him.

To love Jesus is to love him because he is Jesus, the Son of God. This is a Jesus whom we love because we love Jesus. There is no logical explanation. There is no checklist or pietistic formula for determining how one loves Jesus. I love Jesus because Jesus loves me. And Jesus loves me, because I love Jesus. And I love Jesus because I love the Other. And because the Other can love yet an Other, Jesus can love me. Such eroticism is silly, but it nonetheless is bizarrely accurate. To love Jesus is to render one unable to do justice to loving Jesus.

Of course, we don't like to think of love as such because in our insecurity we wish to manage love so that we know when we're actually loving. Whenever we are trying to compartmentalize love, we're trying to hide love, because we fear that we are not loving. And in doing so, ironically, we fulfill our not-lovingness. The lack of love is terrifying and chaotic. And so, we try to constrain it with human rules so that this love becomes manageable. The love of God, in other words, becomes legalism. And, as with all legalistic forms of faith expressions, our measure of faith is judged by how close we follow it. Thus, we publicize our love of Jesus by declaring it and by living it out in the most visual way possible.

What we need, then, is to singularize love, to restore the jouissance of love so that we can love God for the sake of loving God. To love God erotically is to love God fully in all the creativity associated with it. It is this erotic love that forms the basis of the spirituality of St. Teresa de Ávila, Hadewijch of Antwerp, or St. Catherine of Siena. Such erotic love of God is beautiful, sensuous, and singular.

Comments

Post a Comment